Global Trends: Parasite Control in Pets

Last Updated March 2024

Parasites like fleas, ticks, mites and worms are a lifelong risk for pets. They cause pain, discomfort, and disease that can be life-threatening for a pet if left untreated. In addition, some pet parasites can also infest, infect or spread disease to people, which puts our health and well-being in jeopardy. This is particularly important for ‘at-risk’ populations like the elderly, children or immunocompromised where an infection with a parasitic disease like could have severe lifelong health consequences.

This is why parasite control is one of the cornerstones of veterinary care and should be an essential consideration for all pet owners. However, the risk of parasites is growing in many regions. Rising pet populations combined with global phenomenon like climate change is enabling parasites to thrive and spread into new areas.

Parasites can be prevented though. Veterinary expert groups across the world have developed guidelines that leverage tools like diagnostics, vaccines and parasiticides alongside practical hygiene practices to drastically reduce the risk of a parasite infestation or infection. However, surveys show pet owners are often are not aware of recommendations.

This document outlines how the global landscape for parasite control is shifting, where threats may be rising, and what can be done to better prevent parasites from harming pets and people in the future.

Parasites are growing risk for pets

Parasites are found everywhere and can harm both pets and people if left uncontrolled, particularly as parasites spread into new areas.

Parasites are a common danger to pets in many countries

Parasites like fleas, ticks, mites and worms are a common risk for pets. External parasites can lead to irritated skin, bites, hair loss and disease, while internal parasites can cause diarrhea, appetite loss and extreme fatigue.Veterinary ‘parasite councils’ track parasites and have found them present nearly everywhere.

A U.S. study of dog parks found 20.7% of dogs sampled tested positive for parasites1https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-020-04147-6

An EU study found 50.7% of cats tested positive for at least one internal or external parasite2https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-3305-7-291

A study of French dogs and cats found that 15% tested positive for parasitic worms3https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36068597/

A UK study of shelter dogs found 21% tested positive for Giardia4https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20609523/

Households across the world have pets

There are likely over a billion pets around the world and these numbers continue to rise.5https://healthforanimals.publishingbureau.co.uk/reports/pet-care-report/global-trends-in-the-pet-population/ This is driven by younger generations and a growing middle class in emerging markets. These animals provide companionship and comfort but can serve as a growing ‘reservoir’ for parasites if not properly controlled.

Increasing prevalence and geographic spread of vector-borne disease

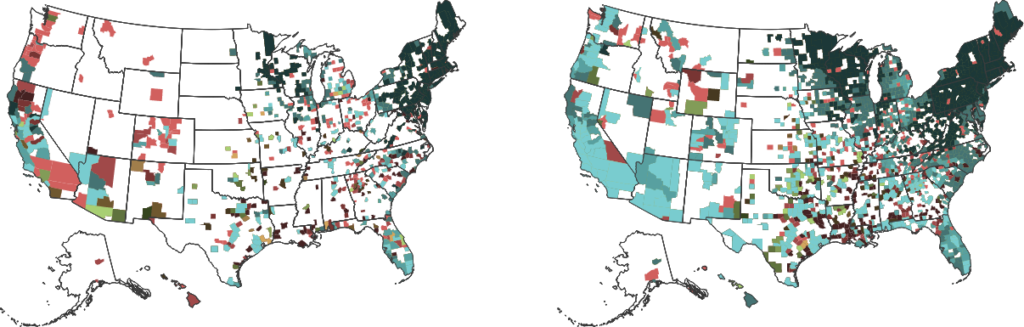

Vector-borne diseases or ‘VBDs’ are illnesses that are spread by parasites to people and animals. Diagnostics data shows that pet screening for VBDs is on the rise across the United States, which is being driven a growing prevalence and geographic spread.

U.S. vector-borne disease screening shows increased parasite detection (2010–2021)6*Map created used internal IDEXX diagnostics data

Global phenomena like climate change are helping parasites thrive

Factors such as climate change and global travel is helping parasites spread and thrive in regions that may not have been hospitable in the past. This means more pets are at risk and veterinarians must stay up-to-date on parasite threats in their area.

The UK’s ‘Tick Surveillance Scheme’ shows canine travel from EU countries is directly connected to the arrival of new tick species7https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29217768/

European countries have experienced a “continuous spread of heartworm disease in the last decade (2012-2021)”8https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/11/9/1042

A global study found that ‘climate change is projected to continue to contribute to the spread of Lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis9https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35585385/

U.S. veterinary experts report that “risk for parasitic diseases continues to increase and expand into areas that have had historically low prevalence.”10https://capcvet.org/about-capc/news-events/companion-animal-parasite-council-releases-annual-2021-pet-parasite-forecast/

Pets can transmit parasites to people

When pets are not protected, the surrounding household is at greater risk

Some of the parasites that harm pets can also infest or infect people. Parasites like fleas can lead to household infestation, while others like ticks can transmit illness (also known as ‘vector-borne-disease) to pets and people. Controlling parasites in pets protects their health as well as the surrounding household and community.

Tick-borne infections in dogs directly ‘correlates with human cases… and the number is increasing’ according to researchers11https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-020-04514-3

If prevention products are not used, a household flea infestation requires 3 months to eliminate, according to the European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites12https://www.esccap.org/uploads/docs/oqsb8b7j_0687_ESCCAP_General_Recommendations_update_v5.pdf

Parasites increase the burden of disease in people

‘Zoonotic’ parasites affect both people and pets, spreading illness and causing physical harm like bites. This can pose a serious risk to people, particularly children, elderly or immunocompromised groups. For example, in Brazil, 7% of human cases of leishmaniosis – a parasite of “major zoonotic concern” where pets can be a carrier – are fatal.13https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0009567#

Parasites & parasitic diseases cause serious harm in people

Three Zoonotic Parasite Threats

Ticks

Can infect pets and people with diseases such as lyme and ehrlichiosis.

Nearly half a million

people in the United States are diagnosed and treated for a tickborne disease each year15https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dvbd/media/lyme-tickborne-diseases-increasing.html

Leishmania

Causes a potentially deadly disease, involving fever, sores, and organ issues.

Up to 40,000

people die from leishmania each year, and human cases are directly correlated with prevalence in dogs16https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352771424000053

Fleas

Year-round issue causing bites, skin irritations, and itching with the ability to transmit pathogens.

1 in 4

cats and 1 in 7 dogs in

the UK may have fleas17https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-019-3326-x

Parasites can be prevented

Parasite control in pets is essential considering the risk it can pose to the animal and the surrounding household. ‘Parasite Councils’ such as the U.S. Companion Animal Parasite council (CAPC) , the European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) and the Tropical Council for Companion Animal Parasites (TROCCAP) provide expert guidelines on effective parasite management. Local authorities and veterinary associations also provide guidance for pet owners to protect their animal.

Although the specific advice will differ by country, all experts generally agree that the best way to protect pets and ourselves is to prevent parasites and parasite-transmitted diseases from establishing themselves in the first place. A few areas that are often recommended include:

Hygiene measures

Experts like the American Veterinary Medical Association recommend ‘good hygiene’ as a simple way to ‘reduce the chances your pet will infect people or animals’ with a parasite. Practices developed by ESCCAP18https://www.esccap.org/uploads/docs/t58tbu33_0687_ESCCAP_General_Recommendations_update_v5.pdf include:

Review parasite control in pets at least every 12 months as part of an annual health check.

Advise the client to cover sandpits when not in use.

Stress the importance of thoroughly washing all fruit and vegetables before eating.

Encourage hand hygiene, especially in children.

Advise the client against feeding unprocessed raw meat diets to pets and encourage the provision of fresh water.

Advise the client to pick up faeces immediately from gardens and when dog walking and to wash their hands afterwards. Stress that dog and cat waste should not be composted if compost is intended for edible crops.

Parasiticide use

Parasiticides can control a variety of parasites like heartworm, intestinal parasites, fleas and ticks and prevent them from infesting an animal. Veterinarians will recommend products and approaches that match a pet’s risk level. Authorities in many countries or regions also provide guidance. Examples of regional and national guidance include:

“Think 12. Show your love for your pets by giving them 12 months of heartworm prevention and having them tested for heartworm every 12 months.”

American Heartworm Society19https://www.heartwormsociety.org/images/Think_12_PDFs/Dos_and_Donts_Fact_sheetAug2016.pdf

“Administer year-round broad-spectrum parasite control with efficacy against heartworm, intestinal parasites, fleas, and ticks. Control of parasites with zoonotic potential is essential.”20https://capcvet.org/guidelines/general-guidelines/

Companion Animal Parasite Council (USA)

“Dogs and cats living in the tropics should be protected from ectoparasite infestations throughout the year.”

Tropical Council for Companion Animal Parasites21https://www.troccap.com/2017press/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/TroCCAP-Canine-Feline-Ecto-Guidelines-English-v1.pdf

Diagnostic Testing

Regular testing for various parasites is a cornerstone of many parasite control strategies as it ensures that the strategy selected by the owner and veterinarian is working, and also helps ensure compliance. Two types of tests that are often conducted are:

Diagnostics provide the foundation for parasite surveillance.22https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352771424000053

Blood test: Diagnostic tools can check for life-threatening parasites such as heartworm and vector-borne diseases like lyme, ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Groups like the U.S. Companion Animal Parasite Council recommend annual blood tests for pets.

Fecal exam: Microscopic, antigen or DNA fecal testing can detect the presence of parasitic infections such as Giardiosis, hookworms, and tapeworms. Many are zoonotic, raising the risk to a pet’s household.

Every pet owner will require their own mix of actions to address the unique risk of parasites to their animal. Hygiene, parasiticides and diagnostic testing typically play a role based on the recommendations of experts, however determining the exact mix requires consultation with a veterinarian. Ensuring pets regularly see their veterinarian must be at the core of any parasite control strategy.

Parasites & parasitic diseases cause serious harm in people

Surveys consistently show that pet owners are not fully aware of the risk of parasites to their animals and many are not in compliance with recommended prevention practices by local veterinary authorities. This highlights a significant need for greater communication with pet owners and promotion of parasite control by veterinarians, policymakers, and other key voices.

Pet Owner Survey Results

Percentage of French pet owners in compliance with best practices in deworming23https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-019-3712-4

Graphic reproduced from study, French national survey of dog and cat owners on the deworming behaviour and lifestyle of pets associated with the risk of endoparasites.

Only 16% of dogs in the Netherlands adhere recommended deworming practices24https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25468379/

97% of UK dogs are in the highest risk category for parasites, yet only 8.6% meet recommended deworming practices25https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-020-04086-2

Only 5.5% of Portuguese cats meet the recommended deworming treatment regiment26https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167587715300118

95% of dogs and 39% of cats in Spain are dewormed less often than recommended27https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7045513/

More information on parasite control in pets

Pet owners should always consult with their veterinarian for the ideal strategy to control parasites in their animals. Furthermore, companion animal parasite councils in major regions can offer important guidelines for proper control.

USA

Companion Animal Parasite Council

Europe

European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP)

Asia, Africa and South America

Tropical Council for Companion Animal Parasites (TroCCAP)

Frequently Asked Questions on Parasite Control

Answers to common questions about parasite control can be found at the HealthforAnimals website in the Parasite Control in Pets: Frequently Asked Questions page. This resource addresses common questions such as what are parasites, how are they controlled, and measures in place to manage tools like parasiticides.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5https://healthforanimals.publishingbureau.co.uk/reports/pet-care-report/global-trends-in-the-pet-population/

- 6*Map created used internal IDEXX diagnostics data

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27